While our genetics team at UCLA dons lab coats to analyze American Kestrel breeding feather samples and create a genoscape, the rest of our Full Cycle crew has been collecting feathers from kestrels across their U.S. wintering range. By matching the genetic signature of these wintering kestrel feathers to the markers identified from breeding kestrel feathers, we hope to be able to map individuals back to their breeding population of origin and to assess migratory connectivity.

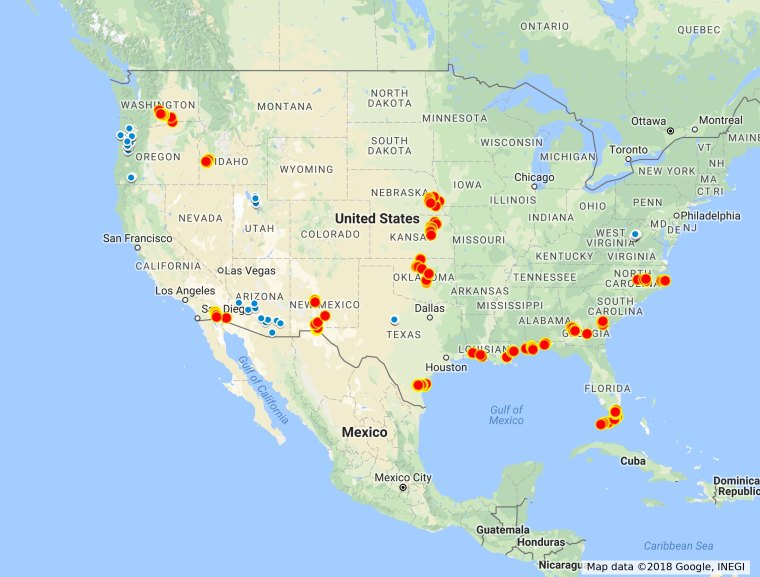

Our first season of winter trapping was a huge success! Our crew collected feather samples from 191 kestrels from 15 states across 3 migratory flyways. We also had collaborators who contributed feathers in Oregon, Arizona, Texas, Utah, and Virginia. We sampled kestrels in agricultural fields, along forest edges, inter-mountain calderas, desert regions, and on coastal beaches across the country.

Map showing the locations that our Full Cycle Phenology crew (red dots) and collaborators (blue dots) sampled feathers from wintering American Kestrels from November 2017-February 2018

We have learned so much in this first year about conducting research across a vast geographic area, and about how much kestrels appear to vary across their wintering range in size, plumage, diet, and habitat associations. It will be so interesting to find out how genetic differences of individuals and the conditions they face in these highly diverse environments affect migration strategy and timing of life cycle events.

Whereas during the breeding season, kestrels using nest boxes are easy to find and hand-capture inside the box, things are a bit trickier during the winter season. Birds may be less tied to a specific area, and they have to be captured using other methods. We used winter Ebird locations (where other birders have seen kestrels) in combination with Google Earth imagery to hone in on the habitat that kestrels are typically associated with, and create rough maps of potential kestrel sampling routes.

When on the ground, we scanned along trees and power lines for perching kestrels. When we spotted one close enough, but not so close as to frighten them off, we placed a Bal-Chatri trap to lure kestrels in. Once kestrels’ legs were caught in the fishing line loops of the traps, we quickly ran over to collect them up for processing.

A pair of kestrels perches on a power pole (left), a female kestrel flies in towards a Bal-chatri trap (center), a male kestrel stands on a trap, likely caught (right). Photo credit: Jesse Watson

We took measurements of each kestrel (e.g. wing length, weight, fat score), attached a uniquely numbered USGS leg band, took photographs for plumage comparisons, and took a few breast/belly feathers for genetic analyses before releasing the bird.

Photographs are taken of this striking male’s back and wing plumage (left), a feather is sampled from a female kestrel (center), view of detached contour feather (right)

Our first trip to the Gulf Coast began with a rare December snowstorm in Louisiana. This was delightful for some locals making their first snowmen, but made for terrible weather to find and capture birds. Luckily, it only lasted a few days. The rest of our trip was filled with kestrels and beautiful scenery. Mississippi and Alabama were prime kestrel areas with lots of wide open cropland and low-use dirt roads. We even recaptured a kestrel in Mississippi that had been banded in Maine in 2016!

A group of turkey vultures cleans a roadkill armadillo in Mississippi (top left), a short break in the rain and snow allows us to catch this male kestrel in Louisiana (bottom left), this recaptured female wintering in Mississippi was originally banded in Maine in 2016 (center), a cotton field provides hunting grounds for this female kestrel in Alabama (right)

The Florida Keys, although beautiful, were so heavily developed and highly trafficked that it was difficult to safely set a trap, while the less developed areas of the Keys were all off-limits federal or state protected land. However, we did manage to catch kestrels near some urban green spaces like marinas and golf courses, and on some of the less inhabited Keys.

A female kestrel caught along a water-lined dirt road in the Florida Keys spreads her wings (top left), one of the many alligators basking near our trapping routes (bottom left), Anjolene holds a male kestrel caught at a forest-cropland edge in the Florida panhandle (center), Jesse displays a male kestrel caught beside a marina (right)

While one crew drove the Gulf Coast, our second crew headed into the Corn Belt in the Midwest (Kansas, Nebraska, and Oklahoma). Kestrels in these wide open and sparsely populated areas seemed to be wary of people, likely not used to seeing anyone down the dirt roads where they perch. They must have had a good prey supply of corn-fed rodents, because these kestrels were the heaviest we caught all season!

Aislinn and Casey hold kestrels caught near a wind farm and a copse of trees in Oklahoma

With the east coast experiencing some of the coldest weeks in history, kestrel sampling was tough and chilly work in Georgia and North Carolina. Kestrels were rarely seen, likely huddled up in trees and structures to stay warm. With perseverance and warm vests, our crew managed to capture kestrels in both states, catching their first bird outside of a peanut factory. They also recaptured a female wintering in North Carolina, that had been banded as a nestling in Massachusetts 3 years prior!

Casey holds a female kestrel found hunting in wet fields in North Carolina (left), Aislinn releases a male on an unusually chilly day in Georgia (right)

The Imperial Valley in California had some of the highest densities of kestrels our team had ever seen! A kestrel on every second power line pole, and empty dirt roads made for prime kestrel trapping. We were lucky to have some fantastic collaborators who have worked in this area for years, to show us all of the best spots. Our team got to see where 2/3 of our winter produce is grown, and were excited to catch a kestrel beside an Aloe field.

An aloe field in California provides hunting grounds for kestrels (left), and Jay holds a lightweight female kestrel in Arizona (right)

In Washington, kestrels were plentiful in areas lined with orchards and vineyards. The team came frustratingly close to catching one beside the aptly-named Kestrel Vintners winery, but were rewarded when they recaptured another female only 10 miles from where she had been banded 4 years prior!

Aislinn and Casey hold a male-female pair in Washington (left), and a female kestrel exhibits strikingly dark plumage

New Mexico was dry and hot, and we had to watch our traps carefully to make sure other raptors (and roadrunners!) didn’t get caught. We caught several female-male kestrel pairs who had no quandaries coming down on a trap after seeing their mate caught. It will be interesting to find out if these birds are year-round residents, or whether they are migrants that have paired up before the breeding season.

A Greater Roadrunner (left) demonstrates its camoflauge abilities in the dry New Mexico fields (photo credit: Anjolene Hunt), a Harris’ hawk scopes the surroundings from a power-pole perch (top right; Photo credit-Jesse Watson), Anjolene and Jesse hold a pair of kestrels caught on the same trap (bottom right)

In Texas, kestrels were not only inland in agricultural areas, but in open wooded areas, and even along the beach near Padre Island! Along with feather sampling of our Texas kestrels, we deployed GPS satellite transmitters on three females. Our transmitters send location data remotely, so we can determine exactly where kestrels migrate and breed, and use this information to validate our genetic methods. Read more about this aspect of the project on the HawkWatch International blog.

Jesse releases a kestrel on the beach near Padre Island, Texas (top left), this large female displays her newly attached GPS satellite transmitter (bottom left), this kestrel shares an open wooded area with cows and horses (right)

As the southern resident kestrels start getting ready to breed, and the migratory kestrels head back to breed up north, our winter season draws to a close. Stay tuned as we head into the breeding season and start our nest box camera project across U.S. Department of Defense installations!

Post by Anjolene Hunt

This study is absolutely awesome! Thank you, thank you!!

Janet eschenbauch

Central wisconsin kestrel research

LikeLike

The transmitter looks great!

LikeLike

Thanks for sharing this information! Its really fascinating to see how the winter trapping efforts went and rewarding to think how our nestling banding and feather collection ties in. Can’t wait for the birds to return to southwest Montana.

LikeLike