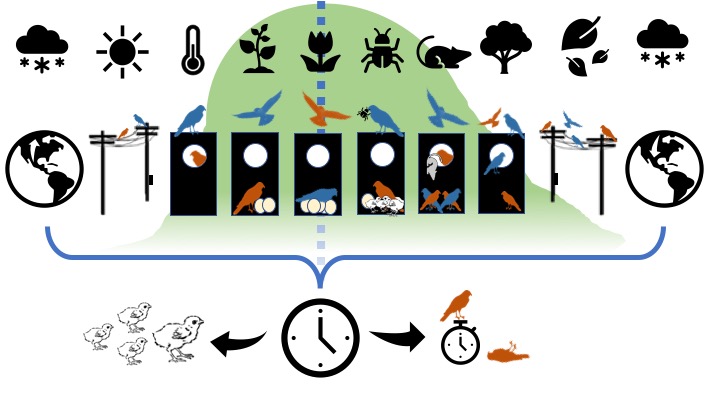

Figure 1. Resource abundance (green curve) peaks during the spring season, following increasing photoperiod and rising temperatures

The amount of resources available to animals changes seasonally, being highest in rainy (i.e. tropics) or spring (i.e. temperate regions) seasons when days are long and temperatures are warm (Fig. 1). Hence, the timing of plant and animal life cycle events- phenology- typically corresponds with the seasons. By matching the timing of resource-intensive activities – such as raising young – with the season of highest food availability, animals can minimize trade-offs between investing energy in the health of their offspring and their own health.

Read about Environmental Factors Influencing Phenology here

Consequences of Mismatch

When the timing of reproduction and peak resource availability is mismatched, there can be repercussions for the health and survival of the adults and their young (Fig. 2). For example, birds that mistime breeding may have lower survival rates or productivity (e.g. number and quality of young) than those who breed on time, a consequence of the resource scarcity, harsh environmental conditions, and extra energy expended by adults on breeding in sub-optimal conditions (Fig. 3).

Figure 2. A visual representation of mismatch between peak food availability (green curve) and kestrel breeding phenology – specifically the incubation (black box with eggs) and brood-rearing stages (black box with nestlings)

One way birds can cope with variable resource availability in unpredictable or changing environmental conditions is to adjust the timing of their incubation behavior (i.e. when parents sit on eggs to promote hatching). Incubation behavior will determine the timing of when eggs in a clutch will hatch, which in turn affects the number of mouths to feed at various times, so parents can use different strategies depending on resource availability.

If resources are plentiful and dependable, parents can wait to incubate until all eggs are laid, resulting in the nestlings all hatching around the same day, and are all hitting their peak-growth rate and energy needs during peak food availability. This can be a good strategy to raise large numbers of nestlings at the time of peak resource abundance.

If resources are scarce or unpredictable, parents may begin incubating the clutch before the female has completed laying the eggs, resulting in hatching asynchrony, in which earlier-laid eggs hatch sooner than later-laid eggs. Asynchronous hatching typically results in earlier hatch dates, and produces nestlings of different maturity levels. It can be an adaptive response to resource scarcity, since nestlings are hitting their peak-growth rate and energy-needs on different days, allowing parents to conserve energy for future breeding seasons.

Figure 3. A visual representation of how the timing of breeding (boxes with eggs and nestlings) in response to start-of-spring indicators (plant, insect, and mammal emergence) can ultimately affect the survival (bottom right) and reproduction (bottom left) of American Kestrels

How Does Changing Climate Impact Phenology?

As climate change results in shifts of the growing seasons, and changes in the timing of seasonal food availability, there is an increased potential for animals to become mismatched with their environment. Shifts in breeding strategies and timing in response to climate change, and the consequences to survival and reproduction are important to understand whether and how populations and species will adapt to changing climate.

The Full Cycle Phenology Project and its partners are collecting range-wide data on breeding timing and productivity. This allows us to sample populations that experience different regional environmental conditions and uneven impacts of climate change.

In our research on American Kestrel phenology, we wanted to know:

- Are there energetic costs for American Kestrels that breed later than the time of peak-prey abundance compared to those that bred in sync with prey?

- Do kestrels modify their incubation behavior to cope with mismatch?

- What are the consequences of mismatch on productivity?

- Could these energy costs impact the survival of mistimed breeders?

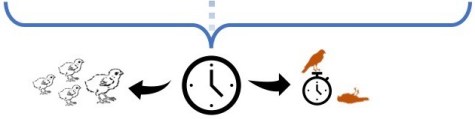

Figure 4. An illustration of the consequences of mismatch of breeding timing with peak resource abundance on the components of fitness: productivity (left) and survival (right)

To assess impacts of mismatch on productivity (i.e. nestling quantity and quality) (Fig. 4), we monitored breeding American Kestrels at nest boxes on Department of Defense (DoD) installations across the United States. We equipped nest boxes with cameras that take hourly photos during the breeding season, so we can determine the lay-date of the first egg in the clutch, and monitor the timing of incubation behavior. For each breeding attempt by a pair of adults, we visit the box to count the number of nestlings, measure the fat and mass of each nestling when they are between 10 and 28 days old. These measurements of productivity (i.e. nestling quantity and quality) will be related to the mismatch in timing between egg laying and the first-bloom date (estimated by the US National Phenology Network), an indicator of prey abundance to determine consequences of mismatch.

To examine the impacts of mismatch on adult survival (Fig. 4), we are using mark and recapture records from long-term monitoring programs in New Jersey, Wisconsin and Idaho (in partnership with J. Smallwood, Montclair State University; and J. Eschenbauch, Central Wisconsin Kestrel Research). In these programs, kestrels have been marked with identifying leg bands, so individuals can be recaptured and identified in subsequent years to determine their survival and productivity over a long period of time. We will create a model of kestrel survival using this data, so that we can assess if mistimed breeders have lower survival rates than birds that breed on time, possibly as a consequence of the extra energy expended by breeding when resources are scarcer. This model will help us predict what a kestrel’s survival probability is based on when they breed.

________________________________________________________________________

RESULTS

For a quick summary of results, check out our blog

OR Read our full published results here:

1) Phenology effects on productivity and hatching-asynchrony of

American kestrels (Falco sparverius) across a continent

2) Seasonal trends in adult apparent survival and reproductive trade‑offs

reveal potential constraints to earlier nesting in a migratory bird

__________________________________________________________________________

Text by Katie Callery (MS Raptor Biology student)

Project: Consequences of environmental synchrony on the reproduction and survival of American kestrels.

Email: kathleencallery@u.boisestate.edu

Literature Cited

- Lack, D. 1947. The significance of clutch size. Ibis 89: 302-352.

- Bortolotti, G. R., and K. L. Wiebe. 1993. Incubation behaviour and hatching patterns in the American kestrel Falco sparverius. Ornis Scandinavica (Scandinavian Journal of Ornithology) 24:41–47.

- Wiebe, K. L. 1995. Intraspecific variation in hatching asynchrony: Should birds manipulate hatching spans according to food supply? Oikos 74:453–462.